It’s been nearly a year since I put out a Compass Point, my longer newsletter segment that is more of a conceptual deep dive rather than an anecdote or check-in. When I first started Cultivar, I thought I’d be able to put one Compass Point out a week … I learned quickly that was too exhausting.

One of the greatest and hardest lessons I’m learning in this pursuit of authentic alignment in my life is recognizing where and what drains my energy, whether emotional or mental.

The most surprising thing for me is that these days, expansive thinking endeavors, such as writing a long form essay, take up way more mental energy then they used to when compared to positive interactions and conversations with people, particularly those who are just as passionate about what they are building as I am.

The intersection of community and creativity is where we find good leadership, and that’s where this compass point is taking us.

The other week I had a very energizing call with Jon Levesque, founder of seeq.ing, I’d highly recommend checking out his vision here.

Over the course of an hour we discussed how he wants to revolutionize the way travel creators monetize sharing their journey and experiences, shared some of our philosophies on AI, what it means to be a true leader, and what the landscape of meaning and leadership will look like beyond our horizon; not in just 10 years, but 20, 30, and 40 years from now.

We both agreed that the future of leadership lies in human connection and authenticity, and though we had a few variations in what we felt it might mean to be perceived as authentic versus resistant to embracing AI and change, there was one statement I made that Jon loved so much he insisted I put out to the world:

“Creativity is the new Commons.”

Despite completely believing in my assertion, and it being one I think I’ve made before in conversation, no one has ever asked me to unpack or explain it; so a huge thank you to Jon for for inspiring my rabbit hole of the past week.

To the leaders current and future that are reading this, I hope you enjoy the following exploration of how our capacity to lead may be threatened by the ever-narrowing ways in which our brains have become rewired for enclosure, hyper-specialization, and efficiency.

It’s a bit long and messy, but I hope you’ll trust me and engage in the comments, because the future of leadership lies in authenticity and regenerative thinking; and systems thinking is modern animism for the corporate world (I’ll explore that last bit in another segment).

History of “The Commons”

“Savoir, Penser, Rêver, tout est là.”

Victor Hugo, Preface: Les Rayons et les Ombres

A Connective and Regenerative Past

// commons: open land or resources (cultural or natural) belonging and available to the whole of a community to ends of both individual and collective benefit.

If you aren’t familiar with the term “commons”, it generally means the land or resources belonging to or affecting the whole community. It’s most commonly (pun intended) been used in my experience and education to refer to the land resources that were available for public use during the Middle Ages up until the advent of both private and personal property.

More than just land for enjoyment, such as our national parks here in the U.S., the commons included water, fisheries, hunting lands, and farmable land for community use and everyday life that, while governed, were not as restricted in who could use them when compared to private land ownership.

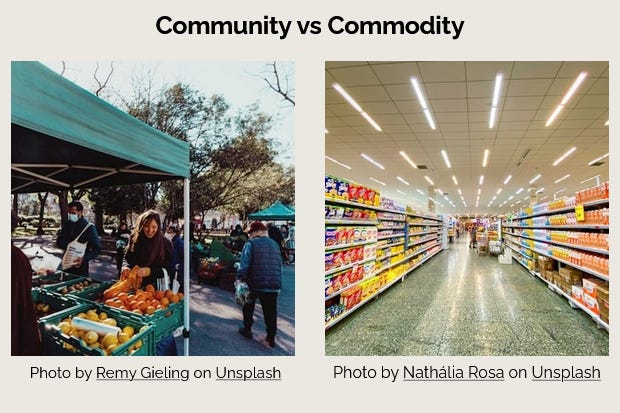

The term originates in a worldview where community was relational, supportive, and self-sustaining; something that, across the board, I see many people longing for.

A semblance of connection that is felt rather than labeled, whether at work or in our personal lives. We are more than our follower counts and org charts.

There are some who romanticize medieval village life because of how far removed our society is from that small, tight-knit sense of being, but on this front, I find a few problems with romanticizing it.

First, what we are chasing is a feeling that we assume we will find if we regain the commons through physical means and intentional living. Assumptions are often the enemy of joy and meaning. Reclaiming the physical commons and living intentionally will only nourish us if we can connect deeply with one another and our surroundings.

Second, the worldview that could have supported that type of intentional living is (nearly) impossible to regain; more than 1,000 years have passed since that time, and our entire conception of being has undergone significant changes (even more so in the past 150 years), something Daniel Lim has come to understand and written about extensively (I would highly recommend reading this article of his: "Building Regenerative Cultures").

A third point of note, is that the concept of the medieval commons are a Eurocentrically focused snapshot of the last breath of the regenerative connective worldview found in early animistic belief structures throughout Europe; other (and often indigenous) cultures from around the world are being studied now by the West in an effort to understand regenerative structures and processes with applications toward urban planning, agriculture, climate preservation, leadership and more.

But that feeling of relating, of community, of belonging, and having a space that you can draw from to support living your life is reified when we try to emulate what was found in the past.

// reification: treating an abstract thing as concrete; particularly in the context of needing to simplify a concept to express an idea.

Feeling connected to a community and of having worth outside of what we provide to our society is absolutely something that can be found and adapted in the modern world; it just takes creative, new ways of thinking that are deeper than what we are used to. There is no way to go back to a medieval-era commons way of living and worldview (absent apocalypse).

In the modern era, engaging in authentic connection and exercising agency in the commons involves challenging the assumptions of our self-awareness and as well as how we relate to those around us. The ones who do this successfully are leaders by virtue of this alone.

As time has gone on, the term “commons” can (and is) applied to a much broader set of understandings than open land for food and natural resources. Healthcare, education, internet access, communication access, and the digital cloud are all examples of intangible yet highly important commons that many people need access to in order to thrive in modern society.

Yet for millions of people, these “commons” are still placed externally to our understanding of self, and we still pay for access rather than having an open door policy for thriving. Why is this?

Because our understanding of the commons and its applicability to creative, authentic leadership is incomplete without also understanding the role of enclosure.

Realities of Enclosure

// enclosure: an area sealed off or separated with a barrier, artificial or natural.

The terms Commons and Enclosure both originate in the English common law understanding of land ownership, with enclosure being a process of appropriating the commons from public use into private or institutional ownership and use, often in the name of efficiency or increased profits.

When the term “public use” is brought up, you might think of access to a park, a river, a community garden, the office breakroom and kitchen, or a public restroom, but there is one often overlooked aspect: agency.

The value of the commons didn’t lie only in its availability for all, but rather in the ability to exercise one’s agency and self-determination in the use of public land.

You didn’t need to ask permission, but you did need to respect the rights of everyone’s access to the commons, because everyone and everything had intrinsic value, and if you took more than you needed, you trampled on the rights of others and upset the balance of regeneration.

Agency must be balanced with discernment, and “a living system is regenerative if it keeps creating more life (itself) or creates the conditions conducive to more life.”1

“A living system is regenerative if it keeps creating more life (itself) or creates the conditions conducive to more life.”

Daniel Lim

The enclosure of the English countryside led to dissatisfaction and riots throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Upon examination of the subtext, it becomes clear that the riots were a response to the erosion of the agency and rights of the common folk to live and thrive in places where they felt a deep, ancestral, communal sense of relation.

As the inability to make ends meet spread, artisans and creative people who lived in more urban environments also began to protest, because the enclosure eventually affected everyone and made them reliant on enclosed systems rather than regenerative open communities.

We often talk about finding our tribe, our people; what we are looking for is a sense of tangibility in both being seen and being impactful; belonging and being. Accepted.

The commons (whether community or resource) serve as a physical representation of our innate right to thrive.

Historically, leadership roles, often thought to be the most “high impact”, are seen as lonely and isolating, but an increasingly larger percentage of people feel isolated despite the connective, communal narrative of social media and increased online presence.2 Whether at work or in person, deep and authentic connection seems harder to find.

It’s worth asking then, if modern levels of loneliness and isolation are an imposed fallacy by the hierarchical nature of the structures most commonly used to enclose different aspects of an organization for control and efficiency.

Perhaps without realizing it, proponents of systems thinking are in fact attempting to reclaim a regenerative, animistic understanding of how people and their environments relate to one another.

The Modern, Intangible Commons

Throughout the 1900s in the U.S., apart from protected places like Yosemite, Yellowstone, and the Great Smoky Mountains, the commons largely shifted from physical land-based resources to those of a digital format.

Work, news, and shopping for necessary (and unnecessary) items are now things we do through an app, rather than touching grass, looking up at the sky, and interacting with our community. To feed and clothe ourselves, we no longer need a direct relationship with the physical commons, nor the people who make the goods or grow the food.

In the 21st century, the disassociation is going one step further.

The cloud, an “enabled network access to a scalable and elastic pool of shareable physical or virtual resources with self-service provisioning and administration on demand,” which provides access to so many necessities with AI, website hosting, and the like, is the current commons at risk of being enclosed.

If you don’t believe me, read this segment of an article from Brian Balfour, who has explored the topic much more in depth than myself:

Once they know what they need, platforms become incredibly generous. They create "open" ecosystems, practically begging developers to build on top of them. Free API access. Viral growth mechanics. Revenue sharing that seems too good to be true.

Why? Because they need you. Your apps, your content, your data, your innovations— they all feed the moat. Every developer or creator who builds on the platform makes it stronger and harder to displace.3

It may not happen to the extent projected, but think of who has access to the cloud versus who has control over it. Amazon, Microsoft, and Google operate the largest “hyperscaled” cloud computing providers.4

If they decide, for whatever reason, to limit (via Balfour’s three step cycle) access to individuals, organizations, or populations in the name of efficiency (maybe you only get to have a certain amount of data storage for the pictures in your cloud drive, or you don’t outright own downloaded movies you’ve paid for), you lose access to the digital commons.

If you are a creator, an entrepreneur, an influencer, a job seeker of any kind, someone who relies on apps to pay your bills, connect with friends, order food or groceries, then you are the commoner to the modern commons. You rely on these digital, intangible commons, these currently available spaces and resources to ply your trade and explore your sense of self.

That sense of self is a form of the commons that exists in our human-ness, our authenticity. Our ability to think creatively, innovate, and build, adapt, and overcome - this is something we’ve always had access to, so long as it is cultivated through new experiences, starting in childhood through education, libraries, community playgrounds, and playing with others (both inside and outside).

I don’t think I need to cite an article to discuss the state of the American education system, but by way of personal anecdote, I have taught a few college classes and have friends and family in the pre-K through university-level teaching professions. It has been our experience over the past 20 years, particularly the past 5, that our capacity to learn, and thereby think creatively, has become severely hampered.

We must ask why (not that the question hasn’t already been posed), at a time when we have the wealth of knowledge at our fingertips, analysis and observation tools beyond the comprehension of Ibn Battuta and Newton, and ability to connect with any perspective on the planet, our youth (and adults) find themselves increasingly limited in its ability to retain and synthesize information, and why we all seem to be facing an authenticity crisis.

My answer to this question is the same to the one I posed earlier on isolation and loneliness: mental enclosure.

Mental Enclosure

I’m a Millennial, and if I’m being completely honest, I’ve had to fight to keep the long attention span I had in childhood over the past 10 years or so, with the intersection of ADHD, algorithmized social media and short-form content, and a traumatic brain injury making it hard to follow through on finishing out creative endeavors.

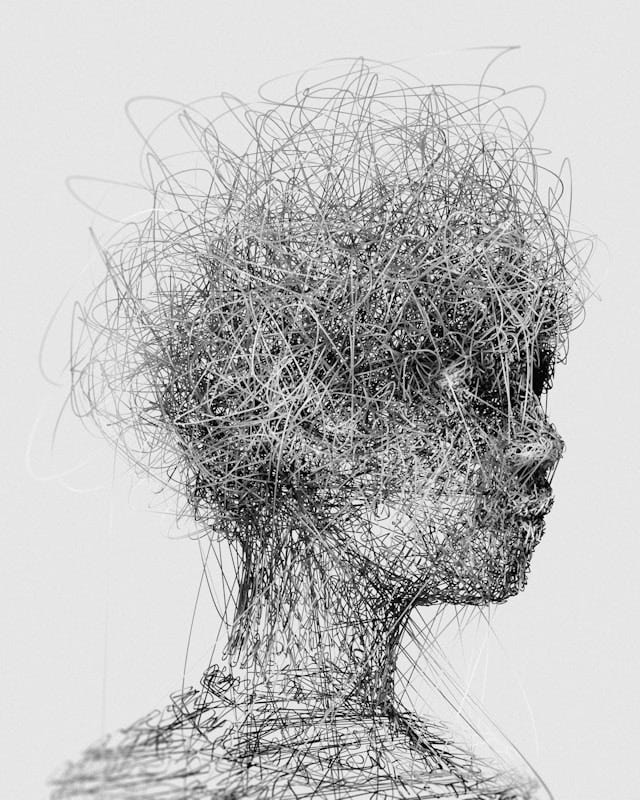

My brain is becoming increasingly enclosed by dopamine hedges masquerading as neural pathways.

I won’t go so far as to say enclosure of the English countryside is the seed that eventually sprouted into the hedge rows of full-blown isolation and mental fog many of us navigate in this digital age, but it certainly looks to be the point at which people began to feel disconnected from the land and their community.

It does seem like a likely candidate for what nudged us to pursue something intangible rather than relational. We’ve confused presence with purpose, and in the exchange are unable to navigate by our own senses.

I remember a time, pre-internet, when I would come up with random stories in my head, write poetry, and brainstorm ways to fix problems with ease.

I would also pay more attention to my surroundings on trips and playing outdoors rather than taking pictures all the time.

I could sit with curiosity and explore options without needing an instant answer. The more I exercised this, the more creative I became.

I think that in a large part, much of my upbringing was rooted in being present in the moment, fully engaged in whatever activity I was doing, whether that was reading, building a fort or Legos, or watching TV.

There wasn’t a sense of needing to know immediately, be connected, and on top of everything, everywhere all at once, and even if there was that drive, I had to explore commons in order to find the answer in libraries, conversation, and experience.

These building blocks set me up to fully explore what lit up my brain on my own terms, how I connected and related to the people and things around me, rather than seeking quick dopamine fixes and instant answers.

I had to sit with things and be present.

Now, the neural hedges are so tall that that even if I wanted to step off the quick and easy path I’d have to expend effort to cut a hole in the hedge, or just keep going. They are something I’ve been trying to cut down with keystrokes and the internal fire of passion projects.

My creativity, my ability to “think outside the box,” was one of my strengths that became evident as I took on leadership roles throughout my 20s. It allowed me to strategize, empathize, and come up with ideas for crises and conflicts without needing to ask someone else, “What should I do?”

I still asked for feedback, opposing views, and perspectives from those on my team, my peers, and higher-ups, but it was to address the blind spots I knew I had, and I could do so because of the relationships of trust I had cultivated.

I only knew I had blind spots, because I had access to and engaged with the commons of creativity; the world of perspective and inspiration that only comes through deep, passionate work, exposure to other points of view, but almost most important of all, the ability to quiet my thoughts and sit still, focusing on the task at hand.

That stillness, that ability to let an answer form rather than appear, was an incredibly important filter that allowed me to see relationships between the commons and my lived experience,

Now, it seems, that my foundations for creative growth have become enclosed.

Stories and poetry don’t always come as quickly or naturally as they used to.

I Google answers to problems rather than looking at the situation first and taking a guess.

I’m always taking pictures on my phone to send to family or friends rather than being present in the moment.

The different components of my human experience are becoming increasingly disconnected, to use a the corporate term for enclosure, “siloed”, something that an excellent writer I subscribe to, stepfanie tyler wrote on recently.5

Particularly as I’ve become a father and a full-time remote worker, if I don’t make intentional space for creative thinking, it manifests in a disjointed manner, and this has drained my energy, bandwidth, and consistency for working and leading.

Through technology (and I primarily blame social media), my ways of thinking and relating, whether concepts or community, have become repetitive, manipulated, and reified; this phenomenon is becoming a stronger and more pervasive force for the generations that have grown up in enclosured digital spaces and mindsets.

Whether optimizing for algorithms, trying to find our voice, or leading others, as a society, we are becoming self-limiting in the name of achieving success and presenting ourselves to the world. My dear friend and mentor, Grace, sent this clip to me other day, and I think it is relevant to the exploration of creativity as the commons:

There is a fine line between understanding something and limiting it. Accepting the answers that AI spits out without critical analysis or engaging with it prior to exercising our own agency runs the risk of enclosing ourselves from the very thing that will separate our intelligence from non-organic intelligence.

Disagree? Let’s have a conversation about it!

Commons and the Future of Leadership

Regenerative Growth is a Mindset, not a Procedure

The moment something becomes standardized, it is limited, enclosed, and the capacity for regeneration is reserved only for those who control the enclosure. Thus, we cannot underestimate the dark power of optimizing for algorithms, templated leadership development courses, or easy labels that tell others what we are rather than expressing who we are.

Even more so, we must be vigilant against letting artificial intelligence do our thinking and our creative work for us. Once we’ve served our purpose with making the digital commons valuable enough to enclose, will our brains be strong enough to build a bulwark to defend the last remaining commons, creativity?

A relevant point from Jon’s latest post exemplifies this:

Platforms operate on extraction economics. They need to capture value to survive. But what happens when the value generators, the creators… realize they don't need those old, harvesting platforms to reach their audience?

When the infrastructure for independence exists? When users prefer human curation over algorithmic recommendation?

These platforms' moat was distribution. That moat is dry. Their castle walls are crumbling. And they're responding by building higher walls instead of recognizing the siege is over.6

What Jon has connected the dots on in both his article and with his vision for seeq, is the connection we are craving in all aspects of life: authentic and sustainable connection. By and large in acceptance of our neural dopamine hedge rows, we don’t value our own authentic selves; we value attention and fitting into the molds society provides.

Capture is the active process of enclosure, a procedure of extraction that removes value from the commons rather than sustainably regenerates it; this happened in the name of efficiency with land enclosure, and it is happening now with the digital commons.

The best example I can think of off the top of my head that illustrates the enclosure of creativity into a commodity is the transformation of Etsy into a hustle culture platform that prioritizes sales over artisans, despite its initial launch as a democratizing effort that traded creative love, labor, and time for profit, rather than relying on storefronts and corporations.

Tying back to Daniel Lim’s thoughts on regenerative culture:

“we tend to exploit things we do not see as sacred.”

What could be more sacred than what makes us human in an era where computers have the capacity to perform scientific and managerial procedures absent our input?

If our very ways of relating, understanding, and creating are extracted for value rather than respected as being an expression and exploration of self, what are we to do against these enclosures?

Once the artisans are gone, will the creative thinkers, writers, and philosophers be next?

“Savoir, Penser, Rêver, tout est là.”

One of my favorite quotes of all time comes from Victor Hugo: “to know, to think, to dream: that is everything.”

To know - we must gather knowledge, whether books or lived experience. Knowledge serves as the foundation of both our authentic selves and our agency in navigating and impacting the world.

To think - knowledge and intellect are not the same. We must be able to critically analyze information in order to form our own opinions and make sense of the world. Thinking involves challenging ourselves as much as others, and it takes active work and engagement to do so.

To dream - the more we know, and the better we can think, the bigger we can dream. Bigger, not in the sense of exponential growth, but bigger in terms of what is possible.

That is everything - those three things and their relationship form the basis of human experience and understanding. So access to knowledge, neuroplastic cultivation of our cognition, and the autonomy to dream as we see fit, while amorphous, are another intangible commons.

As I said, I remember before the advent of social media and short-form content that my brain gathered knowledge and analyzed it differently. I still have the capacity for creativity, and in fact, it’s something I try to cultivate through new experiences, connections, and perspectives, but the soil that fuels my creativity is lacking the nutrients it once was.

I know AI is here, and it is going to become more efficient, revolutionizing many aspects of our world. I know it helps many people and friends in my network ( Adi , Addison (Addi) Fuller 🤠 , and Brie-Anna Willey to name a few) with their work flows, bringing ideas to life and freeing up their time to invest more in things that nourish them.7 But these are individuals who exercise discernment and agency.

My fear is that, AI will be implemented with speed and scale in such a way that proves to be more of a long-term hindrance to the uplifting and empowerment of humanity rather than be a democratizing equalizer for the majority of people.

From an article I read recently, AI has the most usefulness to those who already have a decent level of expertise and critical thinking in a particular field that they are using AI to augment their work in, because they are able to tell when it is wrong.

They are able to question, by way of knowing and thinking, and continuing to dream rather than conform.

So when Jon asserts that he has “increased capabilities 100x in three months via AI”, I believe him, not because of the power of AI, but because of the relationship Jon as an authentic person who loves travel, cameras, Star Wars, and Dragon Ball Z has with AI - his creative, intuitive self with knowledge of disparate arenas of the human experience, knowing where his boundaries lie, what patterns are applicable to surface level irrelevant fields, and how to wield technology to push him further and harness his creativity and understanding.

If Jon didn’t have preexisting depth of knowledge and experience, have rabbit holes of curiosity and passion that intersect in a uniquely Levesquean way, I would expect his capabilities to only increase marginally through the use of AI, and plateau out along with the majority of of people who are adopting and implementing it without a critical or creative lens. I would expect his ideas, his writing, and his goals to be performative copies of everyone around him a la trending TikTok dances and em dashes.

That is my concern for the future; what I think is happening with the majority of our youth, and our current senior-level leadership. Both extremes think the immediate and unquestioning adoption of artificial intelligence its the answer to all the problems they face, whether its bottom line or getting by.

There is no authenticity in AI; all it generates is the amalgamation of knowledge gathered, no new, creative thoughts.

To paraphrase the words of David Baldacci, yes, creatives do read, watch, and synthesize the work of other authors, artists, filmmakers, and so on, but they do not directly copy (unless they want to risk a lawsuit). They get inspired by, they grow and experience life through this process of understanding the diversity of others’ authentic selves and expression.

My fear is that the managerial approach to leadership that so often maintains hierarchies and toxic behaviors extracting value, purpose, and agency will determine the future of how AI is navigated and implemented - I think it is already shaping up to be that way.

If our future generations become increasingly siloed from the creative commons by way of more efficient algorithms, tailored ads, lack of access to basic infrastructure, and intangible commons of education, healthcare, critical thinking, and more, how will they lead? How can we ask them to?

How will they be able to link disparate concepts and see patterns when everything is built to concentrate their thinking according to the busy neural pathways of ease, efficiency, and instant gratification? Will they need to think?

Conclusion

I don’t have all the answers, I’m just seeing connections and trying to make sense of them. However, I do know that we can’t raise leaders who are disconnected and enclosed off from the very thing they are leading.

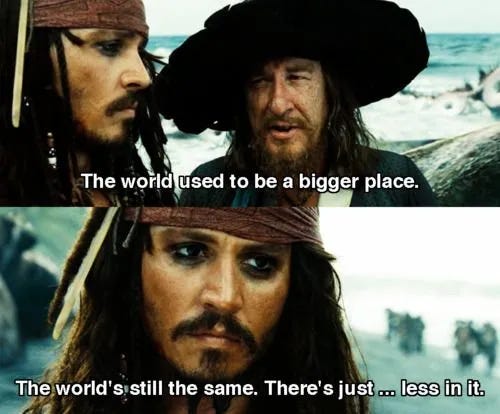

The world is the same size it has always been, yet there is more in it than ever before in our entire history. But it feels smaller, as though there is less, because of our increasing disconnect in how we relate to others and the world.

This disconnect comes from our minds and perspectives becoming enclosed and siloed in ways of thinking that keep us controlled and unable to envision new paths forward.

Technology has the capacity to democratize agency, by and large, I’m not advocating for everyone to become a Luddite; I’ve seen many creative leaders utilize AI with the best intent and to great impact, and I believe Jon is one of them, along with people I’ve worked with like Addison (Addi) Fuller 🤠 .

However, particularly for leaders who are thinking of using AI to get ahead by fitting a mold that makes them feel more acceptable or presentable or implementing AI en-masse to cut costs or compete: tread carefully, and don’t forget that you lead people through authentic connection, not algorithms.

Millennials and younger need community and purpose just as much as they need a paycheck, so show up authentically, and ask yourself the following:

Am I an extractive or regenerative leader?

If you have read this far, thank you for working through this entirely-untouched-by-AI essay.

I intentionally wrote a long form essay to exercise my abilities of “Savoir, penser, rêver,” it took longer than expected and was a challenge to not give up and write something shorter, or narrow down on one aspect of the concepts discussed. But while I still need to be more discerning in my writing, we must dream. That is where hope comes from.

If anything in this Compass Point has resonated, I ask that as you learn and incorporate AI into your processes and workflows, you also lean into your creativity just as much, and that you respect the connections between you and your people.

Explore every facet of connection, feeling, and emotion that you can.

We lead people.

And so we must give equal importance to literature, arts, language, travel, and community - any aspect of life that nourishes our very being and connects us to one another.

Find purpose beyond endless optimization and growth; curate things that inspire you, and share them. Otherwise, what are you optimizing for?

If what makes us human is left behind in our evolution, what remains?

I believe everyone deserves good leadership and that many of the challenges we face in the world today stem from inauthentic, toxic leaders; from extractive structures and behaviors that prize value and efficiency over unlocking the potential in the human race.

To reword Daniel Lim’s excellent quote on regenerative systems:

A leadership approach as a system is regenerative if it keeps creating more leaders (itself) or creates the conditions conducive to more leaders to rise through empowerment and agency.

This is why I believe so strongly in authentic leadership’s role in the coming era.

Authenticity is regenerative. The soil of authenticity is creativity. Creativity is nourished by our capacity to learn, a fundamental aspect of our humanness that allows us to see the relations between disparate concepts.

Because maybe in actuality, creativity isn’t the new, but last remaining commons.

And unless we cultivate it, artificial general intelligence may enclose it entirely.

Thank you so much for reading this exploration of ideas. If something resonated, or if you disagree entirely, I’d love have a conversation with you and hear your thoughts and your story, either in the comments or privately.

You are more than welcome to reach me via chris@cultivarleadership.com, or any of the following:

Cultivar’s newsletters are free, as we believe everyone who leads needs good roots. So if there is someone you know who would get something out of this article,

Footnotes:

https://www.psychiatry.org/news-room/news-releases/new-apa-poll-one-in-three-americans-feels-lonely-e

https://web.archive.org/web/20250118002217/https://www.statista.com/statistics/967365/worldwide-cloud-infrastructure-services-market-share-vendor/

https://substack.com/home/post/p-168610652

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/adikathuria_ai-is-gradually-becoming-my-co-founder-i-activity-7353391758589730816-B0Yf/?utm_source=social_share_send&utm_medium=member_desktop_web&rcm=ACoAABSyMmAB0MFyXJnN4FuNPPPV8XoE4cTi6Ns

Lots to take in here Chris. I wasn’t familiar with the concept of the commons and it has sparked many questions in my head. Most of which I haven’t find words to yet. But I feel you on all of this. Lately I’ve been very aware of my own loss when it comes to focus, allowing myself the space to think and figuring things out, rather than immediately expecting a fully fledged answer. And even to get through this essay (and other long pieces), I have to force myself through the discomfort of a slow pace, because my brain has been conditioned to always expect immediacy.

We are facing complex times. I’m glad there are people doing the thinking to get us through this.

I’ll try to play my part as well 💛